Trouble! was a cabaret-style performance evening and exhibition with a curiosity for the social contract. With performances by Costanza Candeloro with Sophie Vitelli, Luce deLire, Johanna Kotlaris, Inger Wold Lund, Matilda Tjäder and Margaux Schwarz. Objects courtesy of Aisha Altenhofen, Sophie Fitze, Nelson Beer and Costanza Candeloro.

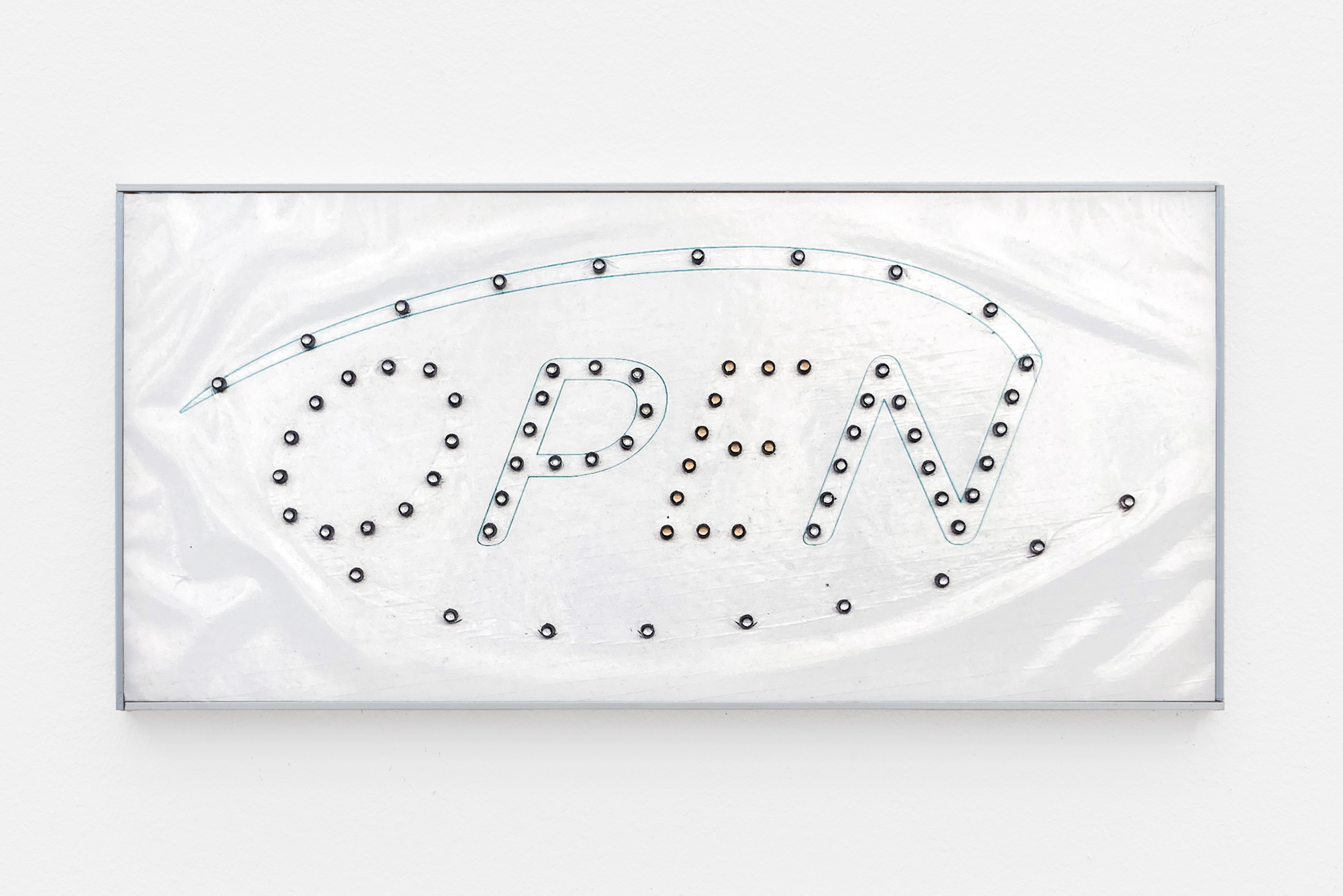

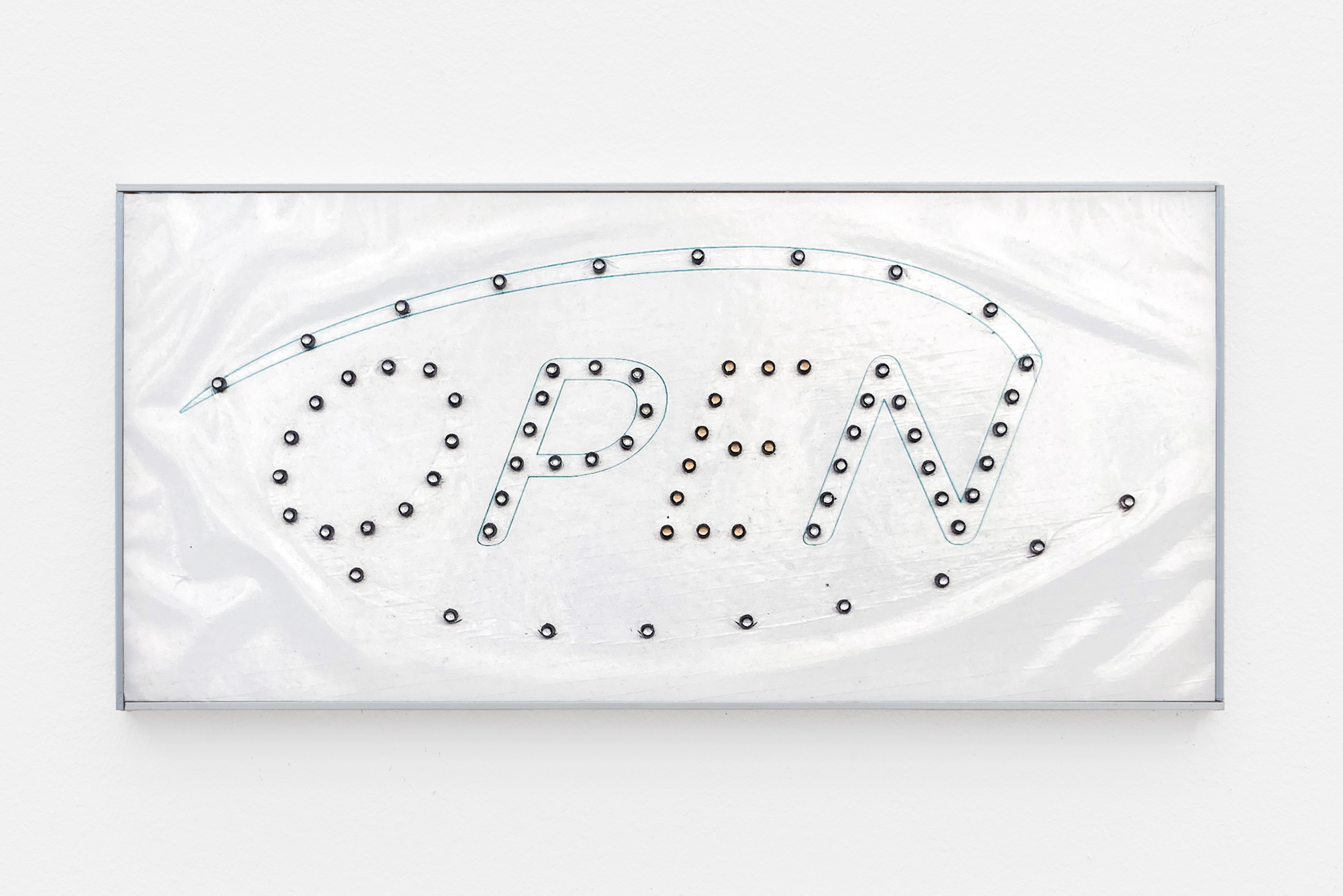

Conditioned Air, 2022

Inkjet Print, artist frame

41 x 19 cm

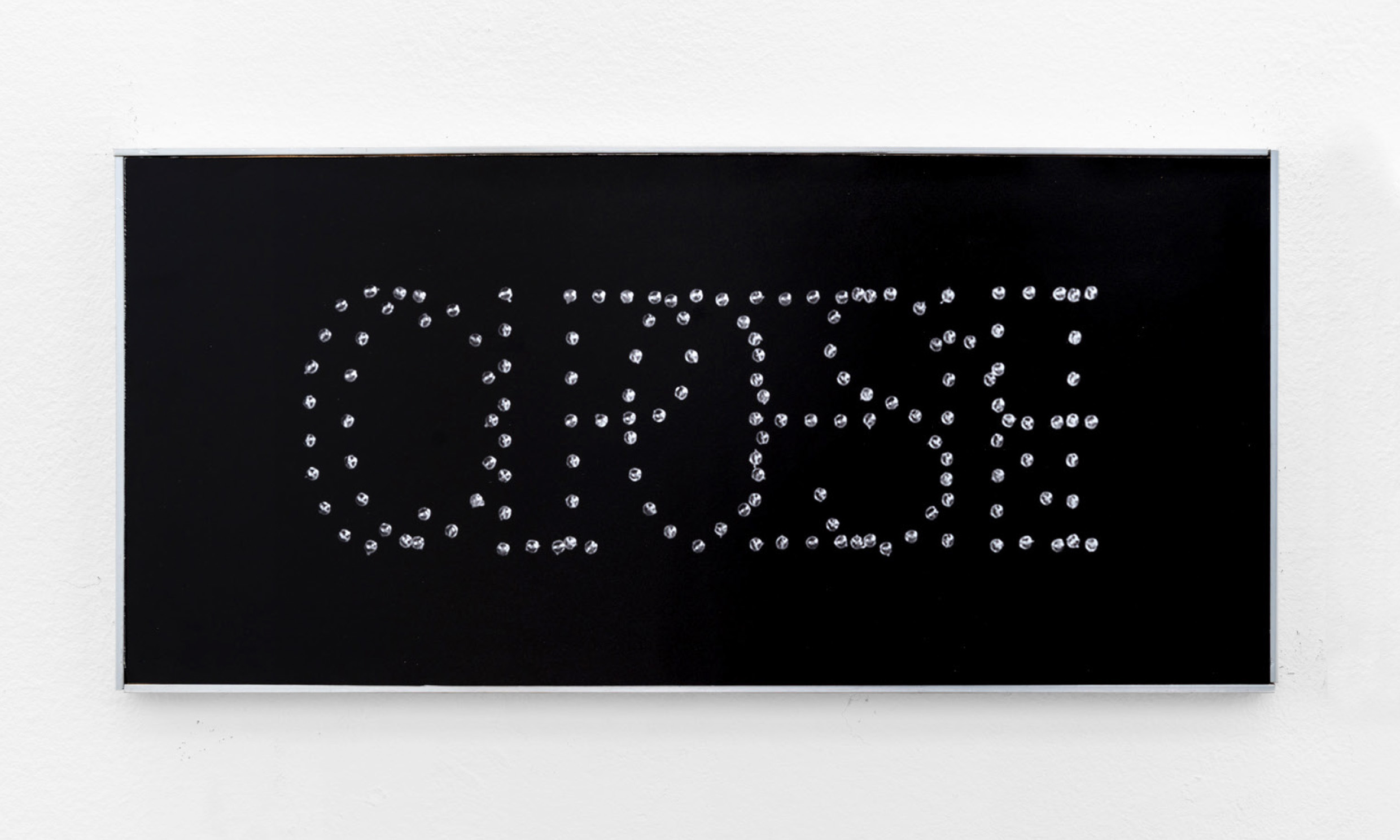

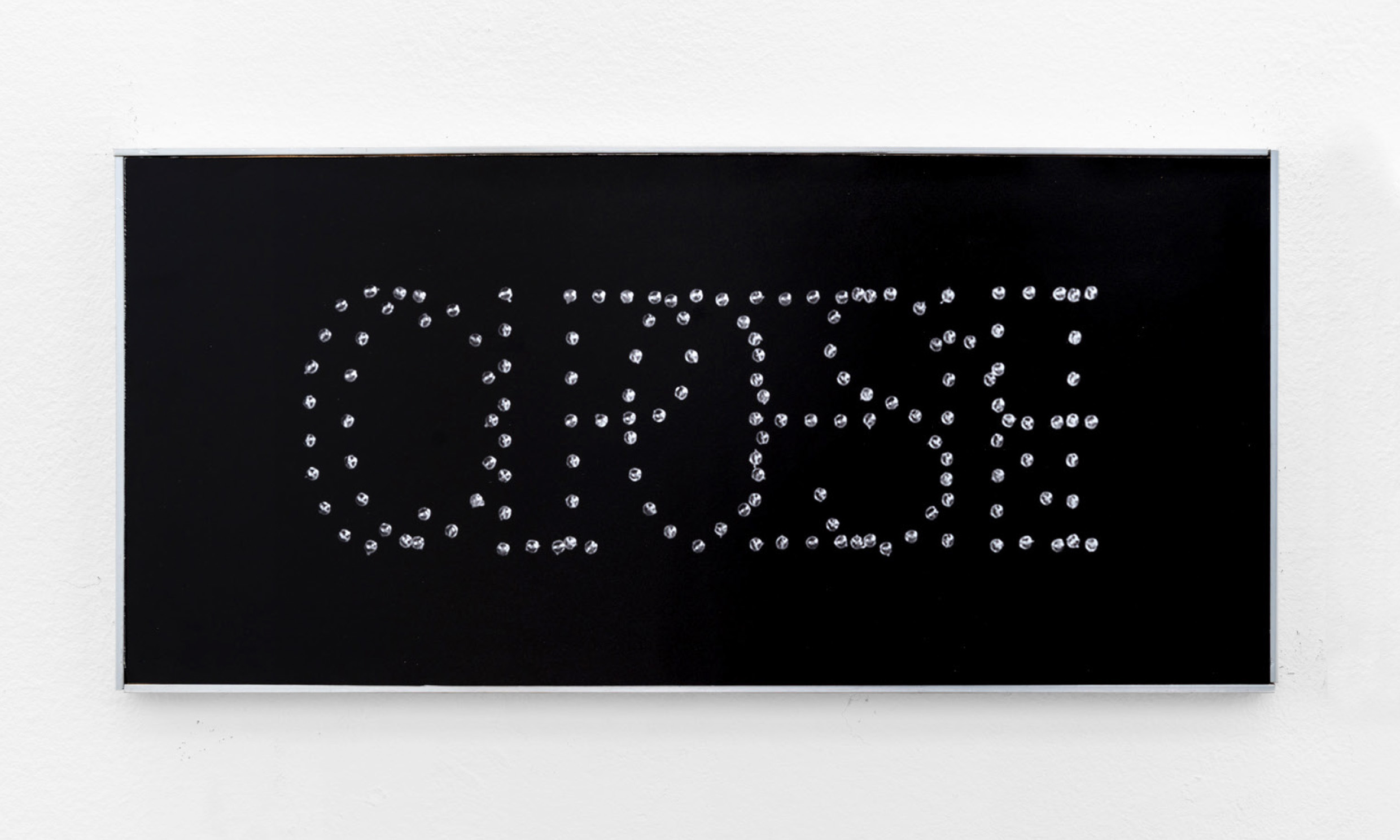

Sky, 2022

Inkjet Print, artist frame

41 x 19 cm

Organised by Nelson Beer

Documentation by Julian Blum